EOS partners with Verona Area School District to support teachers like Kabby Hong and to increase access and opportunity in the district’s advanced classrooms.

By Brennan LaBrie

In April, Wisconsin Governor Tony Evers signed a bill requiring all public schools to teach Asian American and Hmong history, amending a long-standing state law that mandates K-12 education on Black, Hispanic and Native American history.

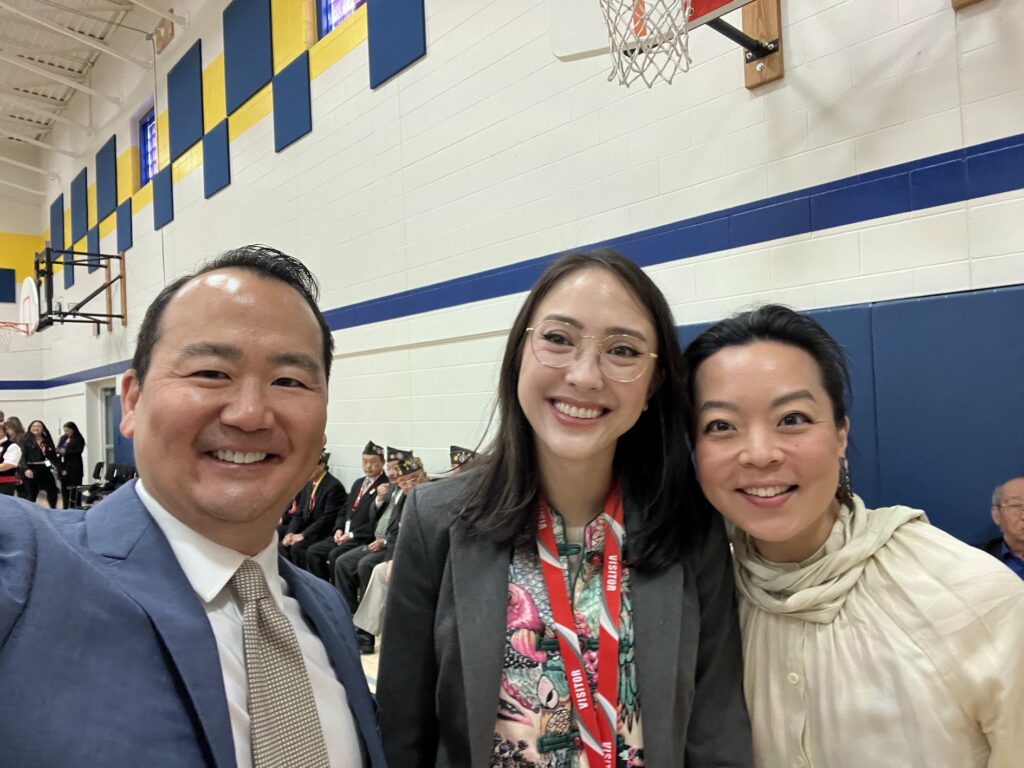

Among those standing beside Governor Evers as he signed the bill was Kabby Hong, an AP Literature teacher at Verona Area High School and a vocal advocate for the new legislation.

Hong, who in 2021 became Wisconsin’s first Asian American Teacher of the Year to represent the state at the National Teacher of the Year Program, used the speaking opportunities this accolade provided to promote the bill – and Asian American visibility at large – to audiences of educators across the state.

“Asian American visibility is a blind spot for all of us,” he said. “If you think about it, you only work on things that are visible and you’re aware of. If something’s in your blind spot, you’re not even aware that you have to work on it.”

Hong also brought students in the Asian Student Association he advises at VAHS to testify in support of the bill at the Wisconsin State Legislature.

“In every single one of their testimonies they talked about feeling invisible, about not feeling like they belong,” he said. “You feel that way as a teenager to begin with, but then if you throw in your racial identity on top of it, it makes it even more challenging. I think being invisible in the school curriculum is sort of symbolic of being invisible in American society.”

These students were well-aware of how important visibility of their community is in K-12 curriculum, he said. VAHS Principal Brian Cox is too.

“Here in Verona Area School District, we really place an emphasis on equity and making sure that, above and beyond just being able to access the grade-level standards every day, our scholars are seeing themselves in the curriculum and have voice and input into what it is they’re learning about,” Cox said. “This legislation really helps aid the mission of schools and school districts like ours – to make sure that our scholars do feel seen, valued and heard.”

Wisconsin has a rapidly increasing Asian American population, and Hmong Americans make up over 29% of it. Indigenous to Southeast Asia, the Hmong were key allies of the U.S. during the Vietnam War and Laotian Civil War. They faced violent persecution in both countries following the retreat of U.S. forces, and thousands fled to the U.S.. Many settled in Wisconsin, in large part due to sponsorships by faith-based organizations. The state now hosts the third-biggest Hmong population in the U.S., following California and Minnesota.

Resistance to the waves of Hmong refugees by predominantly white local populations was a key factor in Asian Americans’ exclusion in the Wisconsin statute mandating curriculum on other immigrant groups, Hong said.

“The bill is essentially trying to reverse a wrong that has been in Wisconsin law for 30 to 40 years,” he said.

Its passage follows two decades of advocacy and multiple attempts by Wisconsin legislators to pass mandates requiring education on AAPI history, including the context behind Hmong immigration to the state.

The tide shifted in 2020, Hong said, when Francesca Hong was elected as Wisconsin’s first Asian American legislator and began advocating for an AAPI education mandate. Additionally, a nationwide wave of anti-Asian American hate crimes during the pandemic prompted states like Illinois, New Jersey and Florida to adopt such mandates.

Francesca Hong credited the advocacy of teachers like Mr. Hong, as well as students and their families, for building momentum for the bill.

Mr. Hong, however, stressed that its passage is far from the last step in the journey of increasing Asian American visibility in school curriculum.

“It was a pretty important symbolic win, but really the real work begins now – and that real work is about making it a living, breathing thing in classrooms,” he said.

Realizing that students could pass through VAHS without reading a book by an Asian American author, Hong pushed for the inclusion such books starting in ninth grade. He is working with school administrators and fellow teachers to incorporate Asian American perspectives into classes across disciplines.

Hong knows that there will be speedbumps in the implementation process.

“The work that’s ahead of us, it’s really about getting districts and individual teachers to explore a blind spot,” he said. “And that can be challenging, because teachers like being masters of their content, they don’t like entering into an area that they know nothing about, or they haven’t had training in.”

Cox is optimistic about the road ahead, however, with teachers like Hong at the helm.

“We need those educators that are strong, not only in the content, but also passionate about issues like this, to help us guide that work and make sure that we as principals, superintendents, etc., are able to live this work and make it a curriculum that is ever-adapting and changing to meet the needs of our teachers and scholars.”

Kabby Hong was featured in several news outlets after the signing of SB240. Read one article here.

Brennan LaBrie helps EOS and its partners tell their stories and spread awareness of their work through the mediums of print, audio and video. With a background in local journalism, he loves sharing the stories of the individuals and organizations driving impact in their community and beyond.